Cyber Security

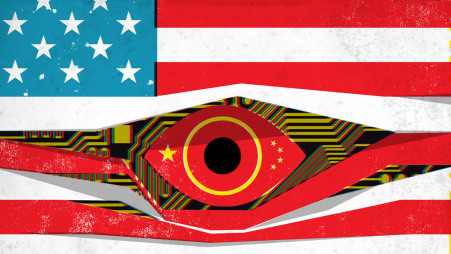

CHINA USED STOLEN DATA TO EXPOSE CIA OPERATIVES IN AFRICA AND EUROPE

Published

4 years agoon

By

GFiuui45fg

The discovery of U.S. spy networks in China fueled a decadelong global war over data between Beijing and Washington.

Around 2013, U.S. intelligence began noticing an alarming pattern: Undercover CIA personnel, flying into countries in Africa and Europe for sensitive work, were being rapidly and successfully identified by Chinese intelligence, according to three former U.S. officials. The surveillance by Chinese operatives began in some cases as soon as the CIA officers had cleared passport control. Sometimes, the surveillance was so overt that U.S. intelligence officials speculated that the Chinese wanted the U.S. side to know they had identified the CIA operatives, disrupting their missions; other times, however, it was much more subtle and only detected through U.S. spy agencies’ own sophisticated technical countersurveillance capabilities.

The CIA had been taking advantage of China’s own growing presence overseas to meet or recruit sources, according to one of these former officials. “We can’t get to them in Beijing, but can in Djibouti. Heat map Belt and Road”—China’s trillion-dollar infrastructure and influence initiative—“and you’d see our activity happening. It’s where the targets are.” The CIA recruits “Russians and Chinese hard in Africa,” said a former agency official. “And they know that.” China’s new aggressive moves to track U.S. operatives were likely a response to these U.S. efforts.

At the CIA, these anomalies “alarmed chiefs of station and division leadership,” said the first former intelligence official. The Chinese “never should have known” who or where these undercover CIA personnel were. U.S. officials, lacking a smoking gun, puzzled over how China had managed to expose their spies. In a previous age, they might have begun a mole hunt, looking for a single traitor in a position to share this critical information with the other side, or perhaps scoured their records for a breach in a secret communications platform.

But instead, CIA officials believed the answer was likely data-driven—and related to a Chinese cyberespionage campaign devoted to stealing vast troves of sensitive personal private information, like travel and health data, as well as U.S. government personnel records. U.S. officials believed Chinese intelligence operatives had likely combed through and synthesized information from these massive, stolen caches to identify the undercover U.S. intelligence officials. It was very likely a “suave and professional utilization” of these datasets, said the same former intelligence official. This “was not random or generic,” this source said. “It’s a big-data problem.”

The battle over data—who controls it, who secures it, who can steal it, and how it can be used for economic and security objectives—is defining the global conflict between Washington and Beijing. Data has already critically shaped the course of Chinese politics, and it is altering the course of U.S. foreign policy and intelligence gathering around the globe. Just as China has sought to wield data as a sword and shield against the United States, America’s spy agencies have tried to penetrate Chinese data streams and to use their own big-data capabilities to try to pinpoint exactly what China knows about U.S. personnel and operations.

This series, based on extensive interviews with over three dozen current and former U.S. intelligence and national security officials, tells the story of that battle between the United States and China—a conflict in which many believe China possesses critical advantages, because of Beijing’s panopticon-like digital penetration of its own citizens and Chinese companies’ networks; its world-spanning cyberspying, which has included the successful theft of multiple huge U.S. datasets; and China’s ability to rapidly synthesize—and potentially weaponize—all this vast information from diverse sources.

China is “one of the leading collectors of bulk personal data around the globe, using both illegal and legal means,” William Evanina, the United States’ top counterintelligence official, told Foreign Policy. “Just through its cyberattacks alone, the PRC has vacuumed up the personal data of much of the American population, including data on our health, finances, travel and other sensitive information.”

This war over data has taken on particularly critical importance for the United States’—and China’s—spy agencies. In the intelligence world, “information is king, and the more information, the better,” said Steve Ryan, who served until 2016 as deputy director of the National Security Agency’s Threat Operations Center and is now the CEO of the cybersecurity service Trinity Cyber. In the U.S.-Soviet Cold War, intelligence largely came in piecemeal and partial form: an electronic intercept here, a report from a secret human source there. Today, the data-driven nature of everyday life creates vast clusters of information that can be snatched in a single move—and then potentially used by Beijing to fuel everything from targeting individual American intelligence officers to bolstering Chinese state-backed businesses.

Fundamentally, current and former U.S. officials say, China believes data provides security: It ensures regime stability in the face of internal and external threats to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). It was a combination of those threats that created the impetus for China’s most aggressive counterintelligence campaign against the United States yet.

The CIA declined to comment for this story. The Chinese Embassy in Washington, D.C., did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Chinese security guards look at military delegates during President Xi Jinping’s speech at the Communist Party’s 19th Congress in Beijing on Oct. 18, 2017. FRED DUFOUR/AFP VIA GETTY IMAGES

In 2010, a new decade was dawning, and Chinese officials were furious. The CIA, they had discovered, had systematically penetrated their government over the course of years, with U.S. assets embedded in the military, the CCP, the intelligence apparatus, and elsewhere. The anger radiated upward to “the highest levels of the Chinese government,” recalled a former senior counterintelligence executive.

Exploiting a flaw in the online system CIA operatives used to secretly communicate with their agents—a flaw first identified in Iran, which Tehran likely shared with Beijing—from 2010 to roughly 2012, Chinese intelligence officials ruthlessly uprooted the CIA’s human source network in China, imprisoning and killing dozens of people.

Within the CIA, China’s seething, retaliatory response wasn’t entirely surprising, said a former senior agency official. “We often had [a] conversation internally, on how U.S. policymakers would react to the degree of penetration CIA had of China”—that is, how angry U.S. officials would have been if they discovered, as the Chinese did, that a global adversary had so thoroughly infiltrated their ranks.

The anger in Beijing wasn’t just because of the penetration by the CIA but because of what it exposed about the degree of corruption in China. When the CIA recruits an asset, the further this asset rises within a county’s power structure, the better. During the Cold War it had been hard to guarantee the rise of the CIA’s Soviet agents; the very factors that made them vulnerable to recruitment—greed, ideology, blackmailable habits, and ego—often impeded their career prospects. And there was only so much that money could buy in the Soviet Union, especially with no sign of where it had come from.

But in the newly rich China of the 2000s, dirty money was flowing freely. The average income remained under 2,000 yuan a month (approximately $240 at contemporary exchange rates), but officials’ informal earnings vastly exceeded their formal salaries. An official who wasn’t participating in corruption was deemed a fool or a risk by his colleagues. Cash could buy anything, including careers, and the CIA had plenty of it.

At the time, CIA assets were often handsomely compensated. “In the 2000s, if you were a chief of station”—that is, the top spy in a foreign diplomatic facility—“for certain hard target services, you could make a million a year for working for us,” said a former agency official. (“Hard target services” generally refers to Chinese, Russia, Iranian, and North Korean intelligence agencies.)

Over the course of their investigation into the CIA’s China-based agent network, Chinese officials learned that the agency was secretly paying the “promotion fees” —in other words, the bribes—regularly required to rise up within the Chinese bureaucracy, according to four current and former officials. It was how the CIA got “disaffected people up in the ranks. But this was not done once, and wasn’t done just in the [Chinese military],” recalled a current Capitol Hill staffer. “Paying their bribes was an example of long-term thinking that was extraordinary for us,” said a former senior counterintelligence official. “Recruiting foreign military officers is nearly impossible. It was a way to exploit the corruption to our advantage.” At the time, “promotion fees” sometimes ran into the millions of dollars, according to a former senior CIA official: “It was quite amazing the level of corruption that was going on.” The compensation sometimes included paying tuition and board for children studying at expensive foreign universities, according to another CIA officer.

Chinese officials took notice. “They were forced to see their problems, and our mistakes helped them see what their problems were,” recalled a former CIA executive. “We helped bring to fruition what they theoretically were scared of,” said the Capitol Hill staffer. “We scared the shit out of them.” Corruption was increasingly seen as the chief threat to the regime at home; as then-Party Secretary Hu Jintao told the Party Congress in 2012, “If we fail to handle this issue well, it could … even cause the collapse of the party and the fall of the state,” he said. Even in China’s heavily controlled media environment, corruption scandals were breaking daily, tainting the image of the CCP among the Chinese people. Party corruption was becoming a public problem, acknowledged by the CCP leadership itself.

IoT security threats highlight the need for zero trust principles

New infosec products of the week: October 27, 2023

Raven: Open-source CI/CD pipeline security scanner

Apple news: iLeakage attack, MAC address leakage bug

Hackers earn over $1 million for 58 zero-days at Pwn2Own Toronto